Blood Pressure

The science of pressure might be too complicated, but when it comes to your blood pressure, it is too easy to understand because, on this page, we have everything you need to understand about your heart and blood pressure.

Start Here

This is the best place to start your education about blood pressure and your hearth health.

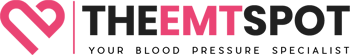

Blood Pressure Chart

Blood pressure may change due to many factors, such as age and activity level. Learn how to monitor blood pressure with this complete blood pressure chart.

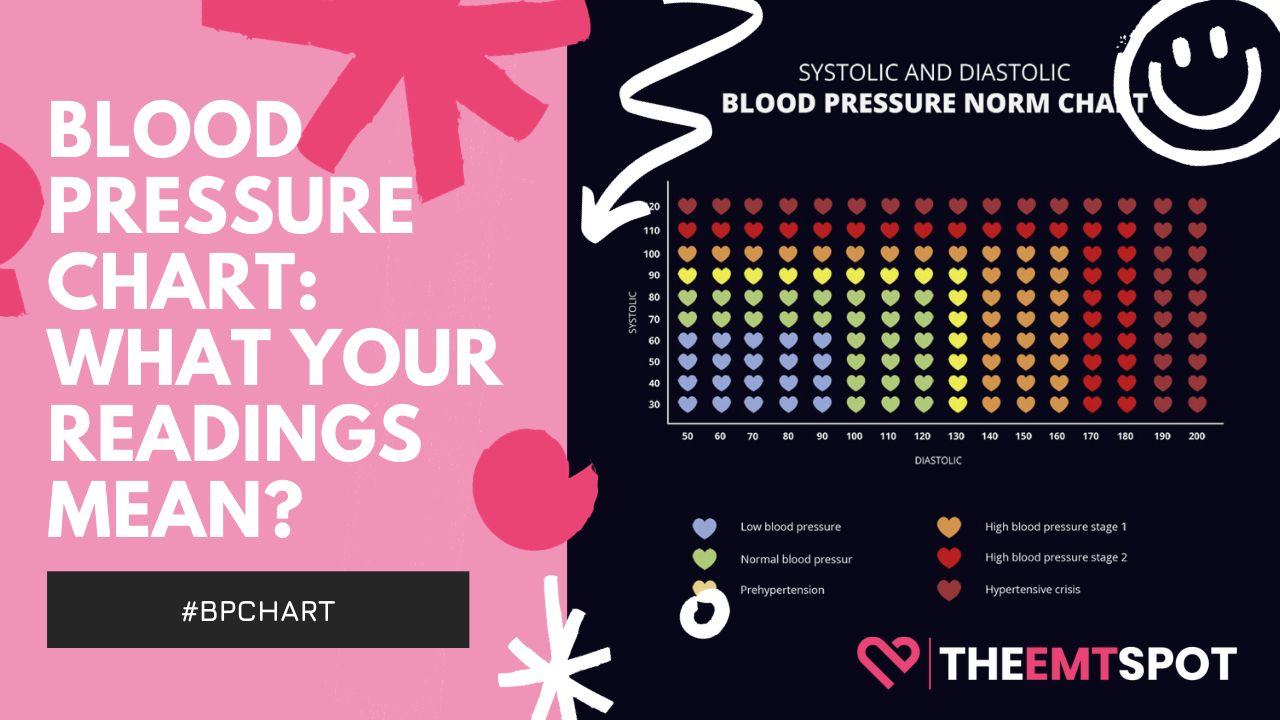

Systolic vs Diastolic Blood Pressure

Explore the critical roles of systolic and diastolic blood pressure, their impacts on health, and which one demands more attention for your wellbeing.

Most Effective Ways To Lower Blood Pressure

High blood pressure may affect your life if you’re not eating well and monitoring your health. Here are some practical ways to lower your blood pressure.

How To Take Blood Pressure At Home

Many people have blood pressure issues and require constant monitoring. Find out how to check your blood pressure at home with ease.

Blood Pressure Medications

Each blood pressure medicine has a different mechanism. Here is a comprehensive list of blood pressure medications available to manage the condition.

Diet For High Blood Pressure

Explore the effective DASH Diet to combat hypertension. Get insights on the best foods to regulate and maintain healthy blood pressure.

High Blood Pressure (Hypertension)

This is your comprehensive guide to understanding, managing, and navigating this common yet critical health condition. Our curated collection of articles delve into the causes, prevention strategies, treatment options, and associated risks of hypertension, empowering you to take informed steps towards better health.

High Blood Pressure (Hypertension)

Learn how high blood pressure can affect your health and some of the things that may trigger it. You will also find ways to manage and control it effectively.

Low Blood Pressure (Hypotension)

Explore our extensive collection of articles on hypotension, commonly known as low blood pressure, encompassing everything from its symptoms, causes, and diagnosis, to various treatments, effective prevention methods, risk factors, and potential dangers.

Low Blood Pressure (Hypotension)

Find out what causes low blood pressure, resulting in hypotension. Learn how to treat and prevent it with some healthy lifestyle choices and habits.

Blood Pressure Monitors

Do you know that your heart can speak to you? Well, not like you are thinking; indeed, you can’t listen to it without proper equipment. A blood pressure monitor is a first and foremost transponder you need to listen to your heart. Dive in and explore some of the best blood pressure monitors on the market.

Best Blood Pressure Monitors For Home Use

Do you know hypertension is a silent killer because you won’t know until you check your blood pressure? Here are the best blood pressure monitors for you.

Blood Pressure Monitors Reviews

Discover the latest advancements in blood pressure monitoring technology and find the best device to suit your needs with our comprehensive overviews.

All You Should Know About Blood Pressure Monitors

Navigate the world of blood pressure monitoring with ease through our comprehensive guides, covering everything from choosing the right device to using it effectively.

Blood Pressure Dietary Supplements

Do you know an average American spends around $2000 to treat their cardiovascular disease? Well, we have pooled a set of heart care & blood pressure supplements that will make this unexpected spending into your savings.

Best Dietary Supplements To Lower Blood Pressure

If you can reduce the risk of getting a heart attack, why wait until something goes wrong? Here are the best blood pressure lowering supplements. More here.

Blood Pressure Supplements Reviews

Take control of your blood pressure naturally with our selection of top-rated supplements, scientifically formulated to support healthy blood pressure levels.

Blood Pressure Medications

Discover the intricacies of blood pressure medications here, where we provide a detailed look at the different options available for managing your blood pressure. Learn about their effects, how they work, and the potential side effects in an easy-to-understand format.

Diuretics

Not sure if diuretics are safe for managing blood pressure? Learn all about diuretics, their potential side effects, and more in this comprehensive guide.

ACE Inhibitors

Do you know that ACE inhibitors are considered a first-line treatment for hypertension due to their effectiveness? Learn more about them in this article.

Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs)

Do you know why Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers are one of the most widely sold drugs on the market? Discover more about its action in this article.

Alpha-Blockers

Your doctor might recommend something classed as an alpha-blocker to manage your hypertension. But do you know what this drug is all about? Learn more here.

Alpha-Beta-Blockers

Alpha-beta blockers are game-changers in cardiovascular care, combining the dual-action effectiveness of both classes of medication. Discover more here.

Calcium-Channel Blockers

Did you know? Calcium-channel blockers excel at treating hypertension, especially in older adults & those of African descent. Learn more about it here.

Beta-Blockers

Dive into the world of beta-blockers: your go-to guide for combating hypertension and safeguarding your heart’s health. Read more about beta-blockers here.

Central Agonists

Central agonists primarily target the brain to reduce hypertension, acting by inhibiting certain nerve signals to lower blood pressure. Read more here.

Vasodilators

Vasodilators widen blood vessels, improving blood flow and reducing heart workload. Learn how they prevent hypertension, angina, and much more here.

Blood Pressure Nutrition

Step into the realm of blood pressure nutrition to discover how your diet can impact your blood pressure. This section offers practical advice, nutritional tips, and food choices that can aid in controlling and maintaining healthy blood pressure levels.

Does Alcohol Raise Blood Pressure?

Alcohol – a friend or foe to your blood pressure? Find out in our comprehensive guide. Let’s sip our way to knowledge!

Does Caffeine Raise Blood Pressure?

Discover if caffeine affects your blood pressure. Our article delves into latest research, offering crucial health information for coffee lovers.

Blood Pressure Management

Unlock the secrets to managing blood pressure naturally in this comprehensive guide. From dietary tips to lifestyle tweaks and beneficial exercises, learn how to harness natural methods to keep your blood pressure in check.

Daily Breathing Exercises That Lower Blood Pressure

If you have high blood pressure but don’t have time or resources for necessary lifestyle changes, daily breathing exercises can make a drastic difference!

More On Blood Pressure

Discover a diverse range of articles providing insights and guidance on an array of blood pressure issues, enhancing your knowledge for healthier living.

Preeclampsia During Pregnancy: Types, Symptoms, Causes and Treatment

Explore the types, symptoms, causes, and treatments of preeclampsia in pregnancy, a serious condition marked by hypertension and proteinuria, affecting 2-8% of pregnancies globally.

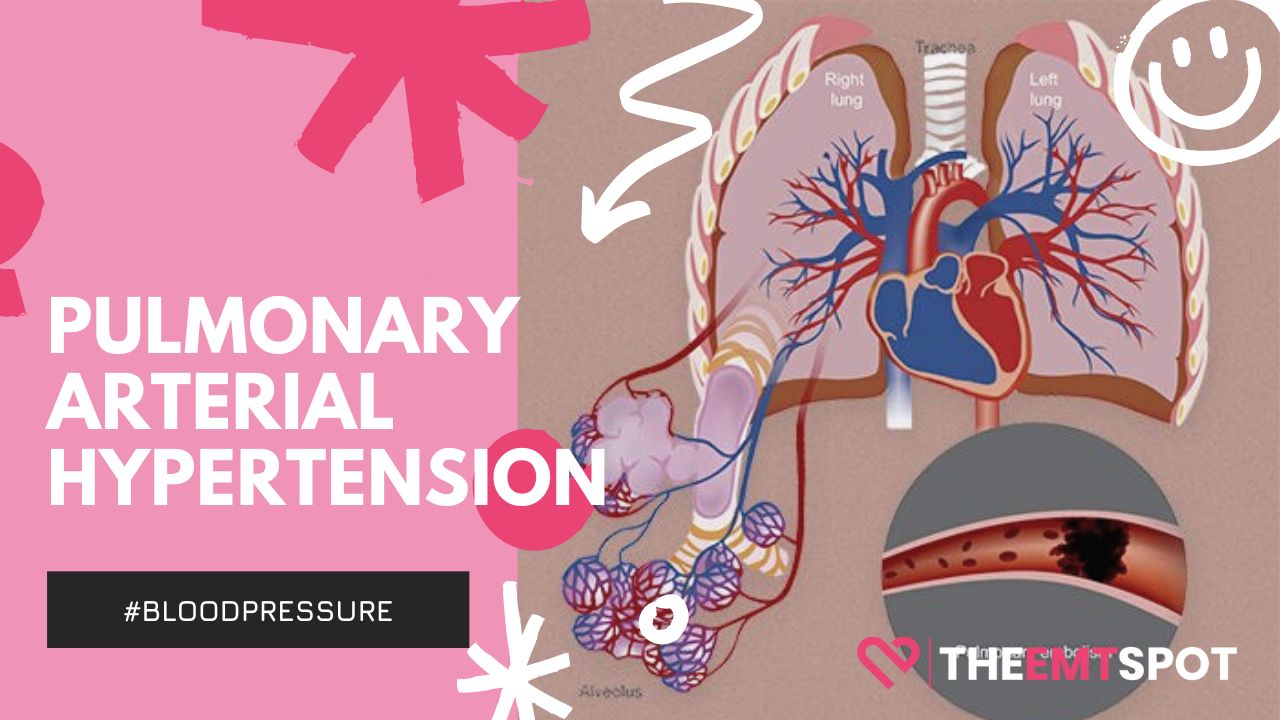

Pulmonary Hypertension (PH): Types, Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

Explore the essentials of Pulmonary Hypertension: uncover types, causes, symptoms, and treatments in our comprehensive guide. Dive deeper into managing this heart-lung condition effectively.